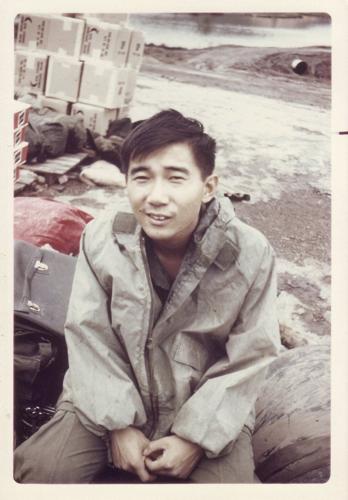

During his adolescence, William Fong's entire world was contained in San Francisco. But in 1967, over a decade into the Vietnam War, he was drafted.

At age 20, he left his home in the city's Chinatown neighborhood for basic training, and then found himself in Asia for the first time. Anticipating he would be surrounded by American soldiers who were mostly white, Fong grew anxious about being perceived as an enemy combatant.

That anxiety only strengthened his conviction and determination to be the best soldier possible, he said.

“I wanted to be accepted like anybody else, not necessarily Chinese or Asian or, you know, from any particular part of the country, but just to be myself," Fong said. He didn't want to be seen as any of the racist stereotypes about Chinese men he grew up hearing.

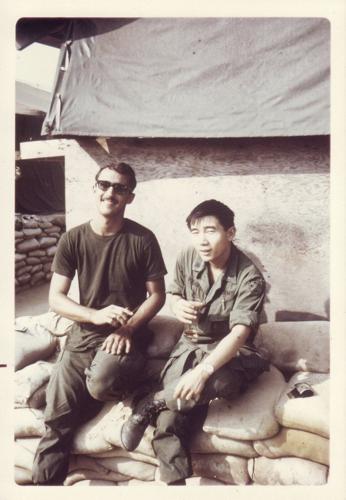

Fong, 77, went on to serve as an armor intelligence specialist during his yearlong tour in , ultimately forming some of the most important friendships of his life.

more Asian American and Pacific Islander veterans are reflecting on the life-changing ordeal that was at times made more complicated by their race. Service members — from the Army to the Marine Corps — are now sharing stories about the racism they faced growing up and again while serving their country. They were often reminded that they resembled “the enemy” and faced hostility and increased violence.

Still, many say they ultimately found camaraderie with their brothers-in-arms and are proud of their service. Now, a half-century later, many of these veterans want their voices to be heard.

Preserving veterans' oral histories

The conflict known in Vietnam as the "American War" began in 1955 when northern Vietnamese communist forces rose in power. It ended on April 30, 1975, when tanks from the north rolled into the South Vietnam capital of Saigon. The U.S. was forced to withdraw. Roughly 58,000 Americans; 250,000 South Vietnamese allies; and an estimated 3 million communist fighters and civilians perished. Out of 2.7 million Americans who fought overseas, an estimated 35,000 were Asian American, according to the Library of Congress.

Since 2000, the Library of Congress’ Veterans History Project has gathered roughly 121,000 submissions of veterans' personal histories. Archivists say only about 700 identified as Asian American or Pacific Islander, but that's likely an undercount since the vast majority of participants didn't disclose their race.

A lot of the credit for those contributions goes to the volunteer-run Asian American Community Media Project, which has submitted over 100 in just the past two years.

The project is a labor of love started by volunteers Don Bannai and George Wada. The Los Angeles area residents, who are both in their 70s and Japanese American, decided to take filmmaking classes for seniors a few years ago. Neither is a veteran. But, both are passionate about preserving veterans' voices. They channeled their newfound documentary skills and personal funds into interviewing and filming veterans' testimonials.

“The hardest thing is to find people to talk to,” Bannai said. “We’ve got a list of 250 guys and a hundred of those have said ‘No, I’m not ready to talk about that. I'm not interested in talking about my story.’ So, that’ll tell you there are other stories out there that are still difficult to tell.”

Looking like ‘the enemy’

Bannai and Wada have dug up fascinating stories of Japanese American veterans who served in Vietnam. Some revealed their parents were incarcerated in camps during World War II. Others had family members who served in the 442nd Infantry Regiment, an that is arguably the most decorated group in U.S. military history.

“The culture that their sons grew up in, of course it was a valid option ... going to serve your country because your dad did or your uncle did,” Bannai said.

Some Japanese American veterans recounted hostile encounters with fellow officers in Vietnam. One recounted a superior pointing to him at boot camp, telling everyone "This is what your enemy is going to look like,” Bannai said.

In one video, a former marine describes how a sergeant hit him on his first night in Vietnam because he assumed he was Vietnamese. The sergeant was then shocked to hear him respond in English. Because of his looks, the man was also prohibited from going on night patrols.

Many veterans who have shared their stories through the project have come away feeling emotional but appreciative of the opportunity to reflect.

“I’m not a counselor,” Bannai said. “But for some of these guys, it’s the first time they’ve ever told these stories. And that feeling of relief, emotional relief, is almost euphoric for some of them.”

Finding commonality in Vietnam

Fang Wong, 77, of East Brunswick, New Jersey, came to New York City from China in 1960 at age 12. Three years later, he obtained citizenship. In 1969, he was drafted. He went to South Carolina, for basic training, then deployed to Germany. Tired of constant snow and homesickness, he volunteered to relocate to Vietnam.

He was stationed right outside Saigon and working military intelligence. The only Asian in his unit, he also found connection elsewhere.

Wong soon found a special kinship with Chinese civilian contractors who worked on the base and introduced him to Cholon, a Chinese enclave in Saigon still considered one of the largest Chinatowns worldwide. He had meals of Cantonese food that were almost "as good as home" and hung out with other Chinese youths.

“Once they find out that I could speak Cantonese, we communicate and every once in a while when we have a chance, I'd go out with them,” Wong said. “I go down to Cholon and find out that they have a bunch of young guys, they play basketball. I happen to like basketball."

Wong went on to serve in the Army for 20 years. In 2011, he also was the first Asian American and person of color elected national commander of The American Legion.

For Fong, a retired grandfather of three living in the Bay Area suburb of Redwood City, talking about the war isn't easy. He saw fellow soldiers die and then returned to the U.S. where the public's perception of the war was contentious. It's hard for civilians to understand, he said. So, he prioritized keeping in touch with fellow veterans. As an active member of the nonprofit Veterans of Foreign Wars' Chinatown Post, he is intent on being a resource available to other veterans.

He hopes these discussions can help other Asian Americans who have served process their experiences.

“Hopefully," he said, "this might give them an understanding that they’re not alone.”