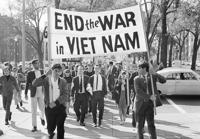

NEW YORK (AP) — Out of the many Vietnam War protests she performed at in the 1960s and 1970s, Judy Collins can never forget one in Washington, D.C., where she stood before thousands and sang Bob Dylan's “Masters of War.”

“It was just me, and Bruce Langhorne playing the guitar, for this huge event. ... And everybody knows the words and very quickly they all start singing along,” she says, remembering the “amazing” spirit of those rallies. “It does trigger something in the brain to hear those songs. They make you say, ‘I must be able to contribute something.’"

The end of the Vietnam War, 50 years ago, also helped wind down an extraordinary era of protest music.

For Collins and such contemporaries as , and bringing the troops home was a mission that carried them around the country, and the world. The journey was shared with like-minded audiences who joined in on “Masters of War,” “Give Peace a Chance,” “Blowin' in the Wind” and other standards — as if to say the songs belonged as much to the movement as they did to the singer.

The causes have endured, and proliferated: arms control and apartheid, women’s rights and globalization, climate change and police violence. And protest songs have been written for them, from “Alright” to “Sun City.” But few, if any, have entered the collective cultural memory like the music of decades ago: Protest songs are as common as ever, protest anthems are rare.

“These days you have all these genres and all of these identities, and things are more decentralized,” says Ginny Suss, who helped organize in Washington and helped found the Resistance Revival Chorus, a collective of dozens of singers who specialize in protest music.

Ronald Eyerman, a professor of sociology at Yale University and co-author of the 1998 book “Youth and Social Movements,” says that it's been a long time since a song like “We Shall Overcome” has emerged, one so universal in its message that it can be adapted to any number of issues. “Protest songs tend to be very specific to an issue and a time and place,” he observes, adding that he can't think of “any anthem related to mobilization about climate change or gay rights.”

The rise of protest songs

The rise of protest music in the 1960s fits into the greater narrative of the post-World War II era. Growing prosperity and young technologies such as television and transistor radios helped give the emerging “baby boom” generation an unprecedented sense of autonomy and common experience, and the Vietnam War and united millions across race and class and geography.

Eyerman notes that the military draft, which ended in the early 1970s, made Vietnam more than just a moral issue for Americans, but one with a “personal, self-interested dimension.” And rock and folk music helped forge a soundtrack of easy melodies and memorable, resonant phrases for an explosive historical moment.

“There was just an incredible intensity of feeling about the political situation,” says Dorian Lynskey, author of “33 Revolutions Per Minute: A History of Protest Songs,” published in 2011. “A lot of people expected an imminent revolution.”

Protest songs in the ’60s and ’70s weren’t only heard at protest rallies: From “Blowin’ in the Wind” to “People Get Ready” to “Ohio,” they also placed high on the Billboard charts.

The current state of protest music

Bill Werde, former editorial director of Billboard and director of Syracuse University’s music business school, the Bandier Program, says protest music still exists in the U.S., but he isn't sure the appetite exists for them as mainstream hits.

He points out that there is a lot of protest music happening outside of the U.S., like that of the popular Iranian singer Mehdi Yarrahi, who shared a song titled “Roosarito,” Farsi for “Your Headscarf,” urging women to remove . He was over a conviction for possessing and consuming alcohol. Or the Indonesian post-punk band Sukatani’s anti-corruption anthem “Bayar Bayar Bayar" (“Pay Pay Pay”).

“It has led to this nationwide call for greater freedom of expression under an increasingly authoritative regime there,” he says of Sukatani's song. “This may be hard for some folks to understand or to accept, but I think one of the simple realities may just be that things aren’t bad enough here in America for people to really feel that urgency, when you compare America to places like that.”

Puerto Rican known for releasing socially conscious music on topics including war, colonization, socioeconomic inequality, and beyond, disagrees. He says that there are contemporary protest songs — you just have to know where to look. For example: “What Happened to Hawaii” in English, a song that ties the U.S. colonization of Hawaii to the Puerto Rican fight for independence.

Last year, Residente released “Bajo los Escombros,” ("Under the Rubble") with Palestinian artist Amal Murkus, dedicated to the children killed by the war in Gaza. “There are not many songs talking about it,” he says.

Eyerman wonders if the recent mass demonstrations against will “grow into a national force,” with a “distinctive protest anthem.”

A divided country

Like the 1960s and 1970s, the country is deeply divided, politically and socially. But Werde otherwise sees a more limited landscape for protest music. He cites the increased consolidation of the music industry and demise of legacy media outlets, which means “today’s hits are smaller than they used to be” and there are fewer opportunities for protest songs to become full-on anthems. The only way that happens is if “things reach a certain point … like with George Floyd and Black Lives Matter.”

Songs played around that time included Lamar’s “Alright,” Childish Gambino’s “This Is America” and Beyoncé’s “Freedom," which came out before Floyd's murder in 2020.

Often, protest songs become anthems because of their reception.

Oliver Anthony’s “Rich Men North of Richmond" is an example, a song with no explicit ties to any political party that became an anthem for Republicans in 2023. “It’s all about the plight of the working man,” Werde says. “It shows you how music can really be manipulative at times and how a lot of politics is all about like marketing an idea whether it’s true or not.”

A possible reason for the reluctance to produce protest songs may be simply that in 2025, "artists, like most corporations, really want to be left out of the political discussion these days because it’s just too risky to their bottom line,” he says.

His most mainstream example of pop music protest is Lamar’s with its nod to Gil Scott-Heron’s early ’70s anthem “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” and its indirect symbolism, delivered in a way that Werde says corporate sponsors had to agree to, and that wouldn’t “leave an enormous part of that audience feeling deeply offended.”

Residente says that when he started his career in the early 2000s, performing political music had real-life consequences: He was banned from playing in Puerto Rico for four years; once, in Venezuela, he was shot at. “To be censored in your own country is horrible,” he recalls. Nowadays, he is still political in his music but has noticed stateside artists tend not to be.

“I hope that in the United States there will be more (political songs),” he says. “It’s weird. Maybe they’re very concentrated on the business.

“Not every artist is going to talk about social awareness,” he adds. He says he hopes there will be more activist groups in the U.S., like Rage Against the Machine or System of A Down.

History reinvented

What were once protest songs have since been stripped of their original context and repurposed for antithetical ends. Creedence Clearwater Revival’s anti-Vietnam War anthem, “Fortunate Son,” was featured at Trump rallies — over the objections of songwriter — and used in a Wrangler commercial decades after its initial release. Dylan's “Blowin' in the Wind” was the soundtrack to a Budweiser commercial aired during the Super Bowl in 2019. anti-George W. Bush hit “American Idiot” has been used by conservatives on TikTok.

“Things live on a fragmented level like never before,” Werde says. Music discovery happens on TikTok, presented without any context. Gen Z has discovered the Irish band , but when “Zombie” plays, they don't necessarily know the history of the Troubles that the song was written about.

Collins, however, says her audiences seem as engaged as ever. Now 85, she still gives some 100 shows a year and still features “Where Have all the Other Flowers Gone” and others in the protest canon, along with such newer works as her own “Dreamers,” about immigrants in the U.S.

“When I sing ‘Where Have All the Flowers Gone’ ... everyone sings it, everyone knows it. I'm kind of astonished when that happens,” she says. “They're not just protest songs. They're songs of life and the journey of life, things you're up against."